What Comes After ECO4? Why the UK Needs a Clear, Credible Successor to Its Energy Efficiency Scheme

The end of the Energy Company Obligation (ECO4) marks a significant moment in the UK’s approach to domestic energy efficiency. Unlike previous transitions between ECO phases, this is not a policy cliff edge or a period of uncertainty about what comes next. There is a clear successor: the Warm Homes: Local Grant.

This change represents more than a rebranding exercise. It signals a deliberate move away from supplier-led delivery towards a locally driven model, with councils playing a central role in identifying households, coordinating delivery, and ensuring standards are met. In theory, this shift has the potential to address some of the long-standing weaknesses of ECO schemes. In practice, its success will depend on how well ambition is matched by funding, capacity, and clarity.

The transition from ECO4 to the Warm Homes: Local Grant is therefore not just administrative. It is a test of whether the UK has learned from over a decade of energy efficiency policy, and whether it is prepared to put local knowledge at the heart of delivery.

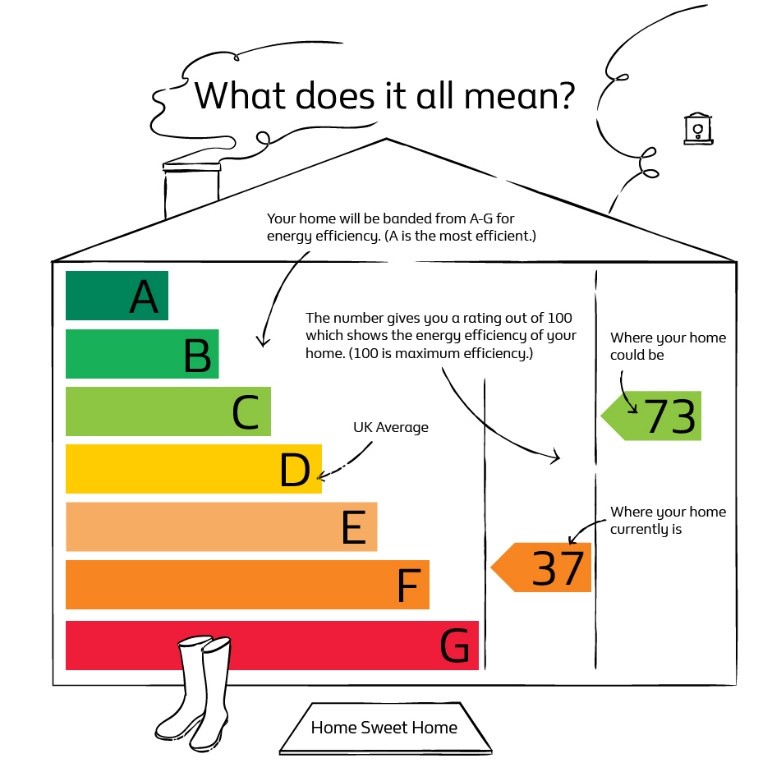

ECO4 was designed to reduce fuel poverty and improve the energy efficiency of the UK’s least efficient homes, primarily through obligated energy suppliers. Compared to earlier phases, ECO4 placed greater emphasis on whole-house approaches and targeted homes with the lowest EPC ratings.

For many households, the scheme delivered meaningful improvements. Insulation upgrades reduced heat loss, heating systems became more reliable, and energy bills became more manageable. During a period of volatile energy prices, these interventions mattered.

However, ECO4 also inherited many of the structural problems that have long affected supplier-led schemes. While outcomes improved in some areas, delivery remained inconsistent, and the experience for households varied widely depending on installer quality, oversight, and local coordination.

The move away from supplier-led delivery under ECO4 was not accidental or sudden. It was the result of years of accumulated challenges that became increasingly difficult to justify, particularly as energy efficiency policy matured and expectations around quality, accountability, and value for money grew.

While energy suppliers played a crucial role in funding improvements, the structure of ECO schemes often placed commercial incentives ahead of household experience. Over time, this created systemic weaknesses that the Warm Homes: Local Grant is explicitly designed to address.

One of the most persistent problems under supplier-led delivery was the lack of clear, visible accountability for households. Energy suppliers held the obligation, but delivery was typically subcontracted through layers of managing agents and installers. For residents, this often made it unclear who was responsible when something went wrong.

In many cases, households had little or no relationship with the energy supplier funding the work. Instead, they interacted with installers they had not chosen and did not fully understand, carrying out work under a scheme they were often only vaguely aware of. When installations were delayed, poorly executed, or left incomplete, residents were frequently passed between installers, scheme administrators, and complaints processes that felt remote and opaque.

This fragmentation also weakened quality control. While compliance frameworks existed, they were often reactive rather than preventative, addressing failures after the fact rather than ensuring consistently high standards from the outset. For vulnerable households, including elderly residents or those with health conditions, the consequences of poor workmanship could be serious, ranging from prolonged disruption to worsening living conditions.

Over time, these experiences eroded trust not just in installers, but in government-backed energy efficiency schemes more broadly.

Supplier-led delivery was, by design, driven by obligation targets. Energy suppliers were required to meet specific thresholds, which created strong incentives to deliver measures efficiently and at scale. While this helped drive volume, it did not always prioritise resident experience or long-term outcomes.

In practice, this could lead to a focus on measures that were easiest to deliver or most cost-effective from a compliance perspective, rather than those that best met household needs. Whole-house approaches were encouraged under ECO4, but they were not always straightforward to deliver within tight commercial and administrative constraints.

This dynamic risked turning homes into units of compliance rather than lived-in spaces with complex needs. The result was sometimes technically compliant delivery that failed to deliver the comfort, affordability, or confidence households expected.

Another limitation of supplier-led delivery was its reliance on national eligibility criteria and centrally defined proxies for vulnerability. While these mechanisms were designed to ensure fairness and consistency, they often struggled to reflect local realities.

Local authorities, housing associations, and community organisations frequently had a much clearer understanding of which households were struggling, including those just outside eligibility thresholds, or those facing multiple overlapping vulnerabilities. However, under ECO4, these local insights were often secondary to supplier-driven delivery models.

As a result, some areas experienced intense delivery activity, while others saw little engagement at all. This uneven distribution not only reduced the effectiveness of the scheme, but also made it harder to align energy efficiency improvements with broader local priorities such as health, housing quality, or regeneration.

Supplier-led schemes tended to operate in isolation from other public services. Energy efficiency upgrades were rarely coordinated with housing repairs, health interventions, or local support services, even though these issues are often deeply interconnected.

For example, cold homes are strongly linked to respiratory illness, mental health challenges, and excess winter deaths. Yet under ECO4, opportunities to integrate energy upgrades with public health strategies were limited by the structure of delivery.

This lack of integration reduced the overall social value of the scheme and missed opportunities to deliver more holistic, preventative outcomes.

The Warm Homes: Local Grant represents one of the most significant shifts in UK energy efficiency policy in over a decade. Rather than refining the existing Energy Company Obligation model, it deliberately moves away from supplier-led delivery and places local authorities at the centre of design, decision-making, and delivery.

This change reflects a growing recognition that fuel poverty, housing quality, and energy inefficiency are not abstract national problems, but deeply local issues. Homes, communities, and housing stock vary widely across the country, and a one-size-fits-all approach has repeatedly struggled to deliver consistent outcomes. The Warm Homes: Local Grant seeks to respond to this reality by giving councils the funding and flexibility to develop programmes that reflect local need.

Under the new model, central government allocates funding directly to local authorities, who are then responsible for identifying eligible households, commissioning delivery partners, and overseeing quality and performance. This marks a clear break from ECO4, where energy suppliers held obligations and local involvement was often indirect or fragmented.

One of the most important aspects of the Warm Homes: Local Grant is the way it reshapes responsibility. By placing delivery in the hands of local authorities, accountability becomes more visible and more accessible to residents.

Councils already play a central role in housing enforcement, public health, and social support. Residents are familiar with them as institutions, and they are subject to democratic oversight. This creates a clearer line of responsibility than supplier-led models, where accountability was often dispersed across multiple private actors.

In practical terms, this means households have a clearer point of contact, better access to local support, and greater confidence that issues will be addressed within a system they recognise and trust.

Local authorities hold rich data on housing conditions, deprivation, health outcomes, and energy performance. The Warm Homes: Local Grant allows this data to be used more effectively to identify households that are most in need of support.

Rather than relying solely on national eligibility criteria, councils can combine EPC data, council tax records, health indicators, and local intelligence to design targeted interventions. This creates the potential for more precise, equitable delivery, particularly for households that may previously have been overlooked or struggled to engage with national schemes.

This local targeting also enables councils to prioritise neighbourhoods or housing types where interventions can have the greatest cumulative impact.

Another defining feature of the Warm Homes: Local Grant is its flexibility. Councils are not limited to a rigid set of measures or delivery pathways. Instead, they can design programmes that reflect local housing stock, climate conditions, and delivery capacity.

In areas dominated by older, hard-to-treat properties, this flexibility is particularly valuable. It allows councils to commission whole-house approaches, phased upgrades, or innovative solutions that would have been difficult to deliver under a centrally defined supplier obligation.

This does not mean the absence of national standards. Rather, it combines clear central objectives with local freedom in how those objectives are achieved.

Because councils are responsible for commissioning and overseeing delivery partners, the Warm Homes: Local Grant creates opportunities to improve quality control and consistency.

Local frameworks can prioritise trusted, experienced installers and encourage longer-term relationships rather than transactional, short-term contracts. Councils can also integrate monitoring, inspections, and resident feedback more closely into programme management.

Over time, this could help raise standards across the sector, particularly if best practice is shared between authorities and supported by national guidance.

Perhaps the most transformative potential of the Warm Homes: Local Grant lies in its ability to align energy efficiency upgrades with wider local priorities.

Energy efficiency can be linked to:

This integration allows energy efficiency to move from being a standalone programme to becoming part of a broader approach to improving living conditions and resilience at a community level.

The transition from ECO4 to the Warm Homes: Local Grant is not simply a technical adjustment to funding routes or administrative responsibility. It represents a fundamental change in how the UK approaches energy efficiency, moving away from compliance-driven delivery and towards a model that treats warm, efficient homes as a public good.

This shift acknowledges a long-standing truth: energy efficiency works best when it is embedded in communities rather than imposed through distant obligations. Local authorities understand their housing stock, their residents, and the pressures facing their communities in a way that national schemes often cannot. Giving councils greater control over delivery creates the potential for more thoughtful, responsive, and humane interventions.

However, this potential will only be realised if the transition is properly supported. Local delivery is not inherently better, it is better when it is resourced, coordinated, and taken seriously. Without sufficient funding, skilled staff, and long-term certainty, councils risk inheriting responsibility without power. In that scenario, the Warm Homes: Local Grant could unintentionally reproduce many of the same problems that limited supplier-led schemes, simply under a different banner.

There is also a delicate balance to strike between local flexibility and national consistency. While councils need the freedom to design programmes that reflect local need, households should not face dramatically different standards or outcomes based solely on where they live. Clear national frameworks, robust monitoring, and meaningful knowledge-sharing between authorities will be essential to prevent the emergence of a postcode lottery.

Crucially, this shift also challenges how success is measured. If the Warm Homes: Local Grant is judged solely on the number of measures installed, it risks repeating the mistakes of the past. Instead, success should be defined by outcomes: warmer homes, lower bills, improved health, and greater confidence among residents. Getting this right requires patience, investment, and a willingness to learn, but the rewards could be transformative.

Energy efficiency policy has often suffered from being invisible. When it works, it fades into the background; when it fails, it becomes a source of frustration and distrust. The move from ECO4 to the Warm Homes: Local Grant offers a rare opportunity to reset not just a scheme, but the culture surrounding domestic energy efficiency in the UK.

At its best, the new approach could normalise the idea that improving homes is a shared responsibility between national government, local authorities, industry, and communities. It could shift energy efficiency away from short-term compliance exercises and towards long-term investment in people and places. This matters not only for meeting climate targets, but for addressing deep-rooted inequalities in housing quality and health.

Yet this opportunity should not be taken for granted. Policy transitions are vulnerable moments. If funding is uncertain, guidance is unclear, or delivery expectations are unrealistic, confidence can quickly erode, among councils, installers, and residents alike. Once lost, that confidence is difficult to rebuild.

The Warm Homes: Local Grant has the potential to be more than a replacement for ECO4. It could become the foundation of a more stable, accountable, and socially grounded approach to energy efficiency. Whether it achieves that will depend on the choices made now: how seriously local delivery is supported, how outcomes are prioritised over outputs, and how consistently lessons are applied across the country.

Warm homes are not a luxury. They underpin health, dignity, and financial security. Treating them as such requires policy that is patient, coherent, and grounded in reality. The shift now underway is worth getting right, not because it is new, but because the stakes are too high to settle for anything less.